Back in the Habit

The Alexander Technique (AT) is a “mind-body” modality. It is one of many, some very popular - yoga, mindfulness - some not as popular, but no less beneficial - Somatic Experiencing, Feldenkrais - but all of these and more address the “mind-body” connection.

I am not a person who is going to be able to change the nomenclature that many folks have been using for years, but I am going to point at the entire idea of “working with the mind-body connection” as a concept that starts off from a place where the mind and the body are separate.

Dear Reader, I tell you they are not.

Or, at the very least, I will say that coming from a place of separation is perhaps not as helpful as coming from a place of integration.

The Alexander Technique differs from the other modalities mentioned above in that AT has within it the five principles mentioned in last week’s blog linked here.

This week’s sermon focuses on this first of the five: “The Recognition of The Force of Habit”

Noting here that “Recognition” is an invitation to think again - to redo one’s cognition - (perhaps another facet of Beginner’s Mind). When looking again at the force of habit what comes up?

Habits by themselves can’t all be bad, some of them are quite supportive of our physical and mental health - looking both ways before you cross the street, flossing, journaling, meditating, reaching out to friends or family - and some of them are less supportive.

What all habits have in common is that they are learned. Drawing that distinction between instinctual and habitual. We are born with the instinct to breathe, we learn, over time, to use the breath in particular ways.

Habits are very efficient ways to move through one’s day. James Clear has a definition of habits that says: “Habits are the small decisions you make and actions you perform every day.” We may have a series of habits that have become a collection - like in the morning where you might be a person who has a “morning routine.”

Skill building is a matter of habit. One learns a skill, then practices the skill, then, over time, the skill automates - there is very little mental effort in holding a fork, but at one point this took some time to get the hang of - habits have a tendency to become unconscious and the unconscious habits rarely get a moment of thought.

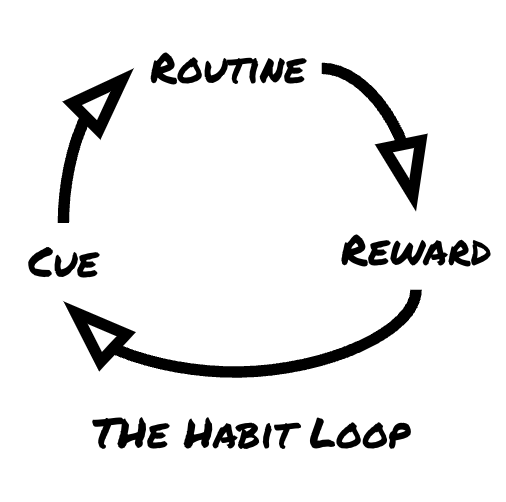

To back up and talk about how these habits get formed - let’s look at the Habit Loop - Dr. Jud Brewer is the person who first introduced me to the Habit Loop that is diagrammed below.

For instance - a growling stomach might be a cue - the stomach growls and one might have the thought “I’m hungry” and that “hunger” might feel “bad” - one might then perform the routine learned in the past of finding food in the kitchen or at the store and then eating that food - the reward being, you are no longer hungry - and that feels “good.”

This might become a habit “if my stomach growls it is time to eat because that means i am hungry and i don’t want to be hungry.” So this loop below begins.

The mind being pretty good at adapting - even if we don’t actually like change all that much - connects this cue directly to this reward when the routine has been practiced enough to be practically unconscious.

And then the fun begins. Perhaps there is a moment when you are not hungry, but you don’t feel great and the mind remembers that there is a routine that historically makes you feel good so, that routine of eating - that is the normal, sustainable reaction to hunger - becomes the routine reaction to boredom, or even minor dehydration.

Over time perhaps the habits (made up of cues, routines and rewards) are not all physically based - the cue is a thought or memory, the routine is a piece of chocolate, the reward is having moved on from that thought or memory. This is a systemic process - this is not the mind and then the body, this is an integrated being moving through life as efficiently as possible under the circumstances.

This shows up in the Alexander Technique - and as AT is of the body this might resonate with your body in this very moment: Humans habitually tense the back of their necks as the first reaction to… almost anything. You reading this right now are invited to ask the back of your neck to release a bit - and then you don’t need to tense it back up.

If you are actively being chased at this time, perhaps a tense neck would allow your body to recognize it is fight or flight time and the ensuing instinctual patterns would commence, but outside of current physical threat, there may be this habit of tensing the back of the neck.

This perhaps started very young, like week 1 not really even focusing the eyes yet young, when you started recognizing a caregivers voice and turning towards it - the neck had to get involved to get the reward of being connected to your caregiver (who was probably holding your head in such a way to protect the neck that was quickly trying to get strong enough to hold it up on your own)

But here we are, however many years later and we now have this capacity to reconsider our habits - we can practice the recognition of the force of habit and when our friend calls to us from across the room and we turn - we don’t need to tense our necks - we do not need to be on guard in a safe space.

You are invited to practice looking at your habits - especially the ones that have become so deeply engrained that you no longer “think” about them - and reconsider if your habits are supporting a greater sense of ease in how you move through your day.

To speak more in person about habits or learn more consider exploring www.balancelab.com.